Miyamoto leaves Nintendo

Fortune's Jeffrey M. O'Brien explains how Nintendo's greatest game designer leaves Nintendo - and beat the pants off Iwata.

By Jeffrey M. O'Brien, Fortune senior editor

December 28 2007: 2:40 AM EDT

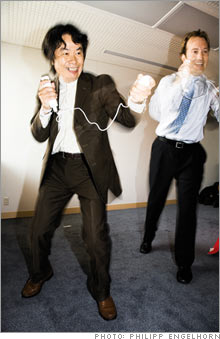

(CNN) -- Nintendo's legendary videogame designer Shigeru Miyamoto is lying face down on the floor in Kyoto, Japan, hobbled by a right cross and struggling to regain his composure. The man some credit with the very existence of the $30 billion videogame industry, the Walt Disney of our generation, has taken one blow to the face too many. I'm standing over the creative force behind Donkey Kong, Super Mario, Nintendogs and his latest worldwide sensation, the Wii. I goad him to get up for the rest of his beating.

Clearly, one of us is taking our boxing match a bit too seriously. After all, it's not really Miyamoto who has crumbled but rather his avatar - his Mii, in Nintendo parlance. "Ohhh" is about all the man can muster as the clock runs out. Miyamoto puts down his controller and concedes defeat to finish a photo shoot.

I may have beaten him at his own game, but we both know who's the real winner here. Nintendo's newest contraption has performed exactly as designed, creating yet another Wiivangelist, this time a gloating gaijin 5,000 miles from home who not only got up off the couch to play a videogame but actually worked up a sweat. With this little victory Miyamoto and company gather more momentum in their quest to conquer worthier competition.

Videogame controllers generally feature a bewildering array of buttons, and watching an avid gamer work the device, thumbs pattering across plastic, can be intimidating. By contrast the Wii's wireless, motion-sensitive remote, which Miyamoto had been dreaming of for years, often requires no button manipulation whatsoever.

In the boxing game my 54-year-old host and I were bobbing and weaving and punching at air - jabs and crosses mostly. Miyamoto, whose official title is senior managing director, would angle his hands from one side to another to avoid haymakers; each time I missed, he'd giggle. And everyone in the room laughed along.

While game consoles typically attract youngish males with an antisocial streak, the Wii is bringing people of all demographics together: in nursing homes, for Wii bowling leagues, on cruise ships, at coed (!) Wii-themed parties and, of course, in lines - as hordes of consumers clamor to buy the impossible-to-find $250 machine. Nintendo is churning out over a million units a month and still can't meet demand.

New recruits

The word "Nintendo" is an amalgamation of three symbols: nin, meaning "leave to"; ten, for "heaven"; and do, "company." The most common translation in Kyoto is "the company that leaves to heaven." What that means is open to debate. It could be a resignation to fate, as in "The company's destiny is in heaven's hands." But it's clear from a series of exclusive interviews with several executives over three months in Japan and the U.S. that little is left to chance. Another translation might be "Take care of every detail, and heaven will take care of the rest."

The man who oversees every detail is president and CEO Satoru Iwata. Iwata, 47, started as a developer for a firm Nintendo bought in 2000. Since taking over in 2002 he has westernized Nintendo, instituting performance-based raises and a retirement age of 65.

To hear suppliers and contractors talk, working with Nintendo is both frustrating and inspirational. It can be Wal-Mart-esque, driving down prices by playing parts manufacturers against one another while challenging them to be more creative. Employees talk breathlessly about loving their jobs while grumbling about hectic schedules. Everyone flies commercial. The one person permitted in first class, Iwata himself, has been known to slog to London and back in one day for a press conference. No hotel required.

In short, Iwata has made Nintendo as efficient as a bullet train and as stingy as a bento box. The company's 3,400 employees generated $8.26 billion in revenue last year, or $2.5 million each.

While exchange rates and fiscal calendars complicate comparisons to U.S. companies, let's do it anyway. Over roughly the same time frame, Microsoft employees generated $624,000 each; Google's performed 50 percent better, at $994,000, though still less than half as well as Nintendo employees. Nintendo's profits reached almost $1.5 billion, or $442,000 per employee, last year, compared with Microsoft's $177,000 and Google's $288,000.

Such gaudy numbers aren't the result of mere penny-pinching. Mainly they're a product of the strategic course Iwata has set. When he took over, PlayStation2 was king, and Microsoft, with its Xbox, was challenging Sony in a technological arms race. But Iwata felt his competitors were fighting the wrong battle. Cramming more technology into consoles would only make the games more expensive, harder to use, and worst of all, less fun.

"We decided that Nintendo was going to take another route - game expansion," says Iwata, seated on the edge of a leather chair, leaning over green tea in a three-piece suit, a strip of gray emerging along the part in his thick hair. He has an easy command of English but speaks through an interpreter. "We are not competing against Sony or Microsoft. We are battling the indifference of people who have no interest in videogames."

The first test of the strategy came in 2004 with the Nintendo DS. Handhelds weren't a new concept. Nintendo had sold tens of millions of Game Boys. But Sony's forthcoming PSP was being touted as a multimedia machine rich in technology and with an ability to play movies. Iwata went cheaper, smaller (the size of the device), and broader (the intended market). The DS has side-by-side screens, one of which is a touchscreen; Wi-Fi; and voice recognition - all to make it approachable and communal.

To put those features to use, Iwata conceived what would become one of the bestselling games for the DS, "Brain Age." Based on the brain-training regimen developed by a Japanese neuroscientist, "Brain Age" tests and improves mental acuity. With sales of more than 12 million copies, the title has made the DS a hit in such unlikely places as nursing homes. Iwata also oversaw development of a talking cookbook "game." And of course Miyamoto kicked in, creating the pet-care game "Nintendogs," which has moved more than 14 million copies. As of this spring the company has sold more than 40 million DS devices, compared with 25 million PSPs. So when it came time to launch the Wii, Nintendo already had a model to follow.

A gaming pioneer

Under Miyamoto's creative direction Nintendo has never had a problem coming up with great games. Pokémon, Super Mario, The Legend of Zelda - Nintendo titles have dominated the bestseller list for each Nintendo console. But that's not necessarily a good thing for the company. Third-party games increase consumer interest in the hardware, which sells more software.

What's more, the console manufacturer gets a licensing fee for every third-party game sold, and it bears no development costs. "It really is pure profit," says Reggie Fils-Aime, the president and COO of Nintendo of America. "Third-party games can really determine who wins."

Fils-Aime, an intense, 46-year-old Haitian-American, introduced the Wii at a trade show in 2004 by announcing, "My name is Reggie. I'm about kickin' ass, I'm about takin' names and we're about makin' games." That opening salvo lit a fire under the gaming media and Nintendo fanboys, and now Fils-Aime is trying to do the same in the game-development community.

More game news

Iwata knows the Wiimote alone won't sustain Nintendo forever. But Tretton's question nicely encapsulates two distinct approaches toward innovation. Despite the fact that the PS2, with its seven-year-old innards, is still the top-selling game console, Sony views the world through the eyes of an engineer, seeing an impressive proprietary technology (Betamax, Memory Stick, Blu-ray) and foisting it on the market.

From that point of view, less technology is always a step backward. Nintendo takes its cues from the outside world - Miyamoto's garden, for example, which was the inspiration for the Nintendo game Pikmin. Or from the behavior of everyday people, like the way we leave our TV remotes on the couch. In Miyamoto's eyes technology is just a tool, and less of it is often more. "What I want to do," he says, "is to make it so people can actually feel something unprecedented."

So what's next for this company, so full of surprises? The Wii gives Nintendo a few options. It could stick with the current Wii for a few years until today's top-end technology falls to Kmart prices. At that point it could introduce a Wii 2.0 with technology similar to today's PS3, but on the cheap. It could cut $50 off the sticker to compete with the price cuts that are undoubtedly coming from Sony and Microsoft.

But that's red-ocean thinking. Iwata wants to keep innovating, to do for gaming what Starbucks has done for coffee or Apple has done for music. "The relationship with the Mac or PC to iTunes and the iPod," he says, "that kind of combination may be possible between DS and Wii."

Until Nintendo gets more Wiis on retail shelves, all that is theoretical. Iwata says no single bottleneck has caused the shortage, and that has made the problem harder to solve. Because it was targeting a market that didn't exist, the company had no idea how popular the machine would be. And nobody could have known the Wii would still be selling so well as summer approaches.

That kind of thing just doesn't happen in the Christmas-centric world of gaming. "We cannot simply make 1.5 times as much or two times as much," he says. "When you're making one million a month already, getting to 1.5 million or two million is not very easy."

Feliz dia de los inocentes

![por aquí! [poraki]](/images/smilies/nuevos/dedos.gif)

![Lee! [rtfm]](/images/smilies/rtfm.gif)

![por aquí! [poraki]](/images/smilies/nuevos/dedos.gif)

pero no creo que gaste bromas este año, ya las he gastado en el trabajo

pero no creo que gaste bromas este año, ya las he gastado en el trabajo

.

. ![sonrisa [sonrisa]](/images/smilies/nuevos/risa_ani1.gif)